Is it a crisis or a boring change?

When Stephen Malkmus and Silkworm went classic rock

In December 1997 Stephen Malkmus was 31 and beginning to show signs of wear. He had spent the majority of the year touring across all of Europe and America supporting Pavement’s fourth full-length, Brighten the Corners. Even by today’s Eras standards, the tour was a sizable undertaking, especially for a cult band often dubbed by the press the kings of SLACK. It began on January 19th at the Red Box in Dublin, Ireland and concluded at the Little Five Points Pub on October 12th in Birmingham, Alabama. In between, there were nearly 75 other performances at a variety of venues, from mid-size clubs to massive commercial festivals like Lollapalooza and Pukkelpop. Particularly amusing is Germany’s Bizarre Festival which boasted a lineup that can only be described as absolutely deranged, its bill featuring the likes of Marilyn Manson, blink-182, Veruca Salt, Bloodhound Gang, Paradise Lost, and, of course, our boys Pavement. (I relish the idea of Stephen Malkmus sharing German finger food backstage with Tom Delonge, two Cali oddballs occupying different sides of the same error coin.)

By the end of Brighten’s tour, Malkmus was exhausted—with road life, with the idiosyncrasies of his bandmates, with doing press, with the Atlantean duty of leading a band that was never really supposed to be a band in the first place. He shaved his head (never a good sign) and began ghosting scheduled interviews. “The only people I’m going to hang around with are…Henry Rollins and some soccer players,” Malkmus joked at the time. The 1997 tour proved to be the beginning of the end; Pavement called it quits permanently in 1999 after releasing one more record. For a more immediate glimpse into the drama of Pavement’s breakup, peep this uncomfortable interview with the now-defunct Canadian music television channel Much.

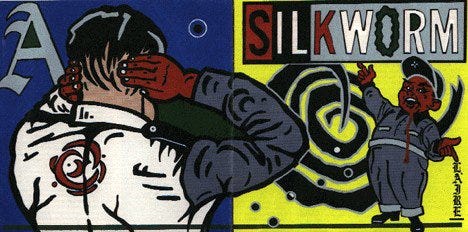

I think it’s safe to say that December 1997 was a different time, however, for a band sometimes obscured by the shadow of Pavement—Silkworm. Started by Tim Midyett, Andy Cohen, and Joel RL Phelps in Missoula, MT, Silkworm spent the late 80s and early 90s doing what it takes to become the stuff of scene legend. They toured by van nonstop throughout the States. They released an indeterminable amount of singles, EPs, and splits. They moved to Seattle. They obtained a real drummer (the sui generis Michael Dahlquist), and they hit the studio to record with fellow Missoula legend and producer extraordinare Steve Albini. They cultivated an indefinable sound by reworking the conventions of indie rock with choices more familiar to unfashionable genres like speed metal and classic rock. As the Pitchfork review for 1994’s In The West puts it, Silkworm were “too heavy to slot next to other indie rock of the time, not heavy or self-serious enough to hang with the post-Nirvana grunge set.” A perfect recipe for a scene’s best kept secret.

But let’s get to back to winter ‘97. As I mentioned, this reads like a good year for Silkworm. Now operating as a trio comprised of Midyett, Cohen, and Dahlquist, Silkworm were fresh off the success of two A+ efforts: 1996’s Firewater and 1997’s Developer. Produced by Albini and released through Matador, both albums marked back-to-back breakthroughs for the band, creatively and (semi-)commercially; each managed to simultaneously tighten and expand Silkworm’s raw, inventive angularity, elevating the boys to new heights. They began selling more records and sharing bills with indie titans like Guided By Voices and Spoon. “[Firewater] did reasonably well; certainly it sold much better than any of our previous releases,” Midyett told fans in an e-letter posted to Silkworm’s website in 1997. Silkworm would never explode in popularity in the way other Matador and Matador-adjacent artists did, but they continued producing under-the-radar gems until 2005 when Dahlquist was killed tragically in a car accident. (For a more comprehensive history of Silkworm I recommend watching the excellent and touching documentary Couldn’t You Wait?.)

At the risk of leaning into fanboy conjecture and constructing false history, I think we can consider 1997 as something of a watershed for both Silkworm and Pavement. Malkmus was exhausted; Midyett, Cohen, and Dahlquist seemed totally energized. It is this polarity I find so interesting about December 1997. On the 5th of that month and that year, Malkmus and Silkworm came together as The Crust Brothers to perform classic rock standards at the Crocodile Cafe in Seattle for a benefit concert hosted by the Washington Wilderness Coalition. Recorded as a one-off CD titled Marquee Mark (lol), the performance not only rips but also offers a glimpse into what 1997 could have felt like for both artists.

Right from the get-go, Malkmus and Silkworm sound determined to sideline the reputations of their bands, particularly Pavement’s. Responding to an audience member requesting they play a Pavement all-timer, Midyett says, “that’s not gonna happen. We’re not gonna play ‘Summer Babe.’” As they launch into the first song of the set, Dylan’s “Going to Acapulco,” the audience likens the opening riff to Pavement, only to have Malkmus halt his playing and deadpan, “That was not ‘Range Life.’” By the song’s end, Midyett offers an ultimatum: “Next person who yells out a Pavement song or Silkworm song gets hit over the head.”

While the Brothers’ chiding is all in good Gen X fun and probably in some part motivated by Malk’s and Silkworm’s simple desire to appear onstage singularly as The Crust Brothers and nobody else, these moments of dismissal seem to inspire the band, especially Malkmus. After dishing out rebukes in “Acapulco,” the boys lock in and absolutely tear through the American songbook, covering lots of material from Dylan’s Basement Tapes and select cuts from Lynyrd Skynyrd, the Stones, and The Byrds. The Silkworm trio continues their hot streak here, demolishing classic rock arrangements with tough, loose shredding that sounds like both homage and progression, an attempt to marry the 70s with the 90s by cranking up to 11 the riffs of yesteryear. By the second time Malkmus assumes the mic in full to cover (hilariously) Silkworm’s “Never Met a Man I Didn’t Like,” he seems genuinely thrilled to be playing anything other than a Pavement song. “Down on Kettner Boulevard, I called on my friend Gerard / Said Cosloy, ‘lend me two million bucks, it's been a decade since I had a good fuckkkkk,’” he sings, revising Silkworm’s original lines with a puckish wink toward Matador cofounder Gerard Cosloy. Directly after “Never Met,” they dive into the best performance of the set, a revved up take on “Heard It Through the Grapevine,” which I can’t even describe. It’s just money, baby. Greil Marcus went so far to call it “the best version of the song ever played.” The rest of the show does not let up.

Part of the appeal of listening to live albums stems from the thrill of vicarious experience; we love being there. But our enjoyment also lies in gaining probably-false perspective into what was going on with our favorite bands behind the scenes during certain eras. I must admit I am often excited by this voyeuristic quality when it comes to recorded live music. Sonic Youth’s Live in Brooklyn 2011, for example, is such a gnarly show because it carries with it the tension of Kim Gordon and Thurston Moore’s failing marriage. Likewise, Phish’s 2/28/03 performance is a classic because it brings forth all the chaos of a band spiraling from the pressures of success. These are crass admissions, I know, but they contain a sentiment that I think is fairly universal among music dorks, whether we’d like to admit it in print or not.

With this in mind, Marquee Mark sounds to me like a key and somewhat forgotten document of transition. For Silkworm, it’s a moment of actualization, the sound of a band gaining complete and unfettered entry into the gilded annals of the indie rock pantheon. They can shred the greats with a great because they themselves are indeed great. For Malkmus, it marks an encounter with a second wind, a re-ignition of a spark that was fading under the weight of Pavement.

A suspicious or cynical reader could call me crazy or cringe for apprehending a one-off live record in this way, and I’d be sympathetic to such an assertion. But I also wish to argue that the embarrassing fantasies we ascribe to recorded live music are precisely what make the aesthetic experience of listening to music so pleasurable in the first place. As we listen to our favorite songs, we do not sit still as passive observers. Our imagination engages with the music actively, dismantling the whole to fashion it anew with elements of the original. We create the songs we love. This is so evident in the case of live records.

Marquee Mark could very well just be the product of four dudes in a room together playing their favorite tunes after a couple of pints. I’m sure that’s how Malkmus and Silkworm would have it. But to me it sounds like two Gen X greats locating the address to the next million dollar bash.

Buy an original copy of Marquee Mark here. Hurry, there are only three remaining. Plus, check out their covers of NFL fight songs here.

Will read later

mentally refashioning music as it’s played - works so well with the ramshackle live cover set. interesting that their live set consists of covers. we get a tertiary reconstruction