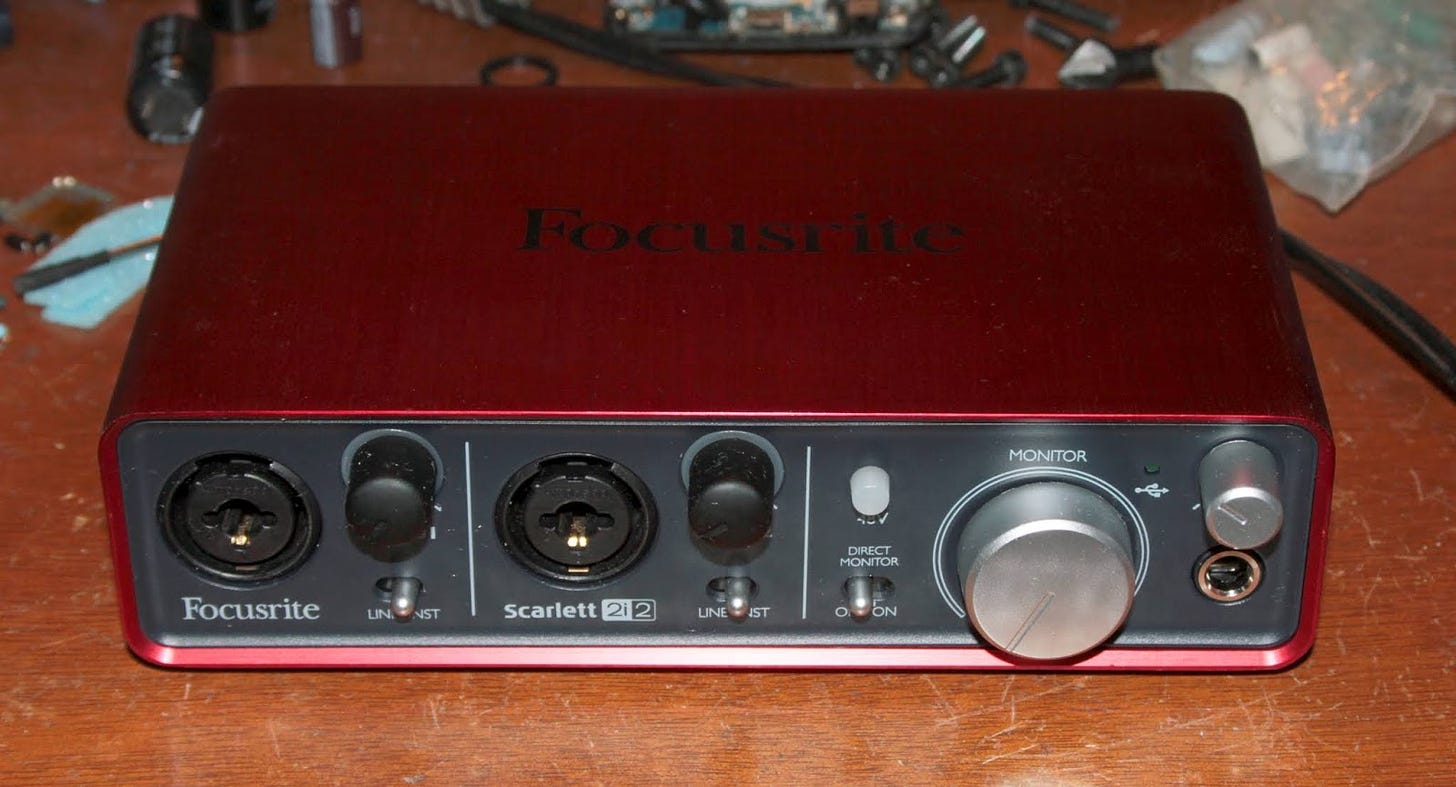

For anyone acquainted with music production and with alternative culture since the early 2010s, the story of the Focusrite Scarlett 2i2 is quite intelligible if not readily top of mind. Launched in 2011, the 2i2 revolutionized at-home audio engineering by providing amateur musicians with an affordable, reliable USB audio interface that simplified the recording process and eliminated the need for cumbersome digital mixing boards and their confusing panels of knobs and faders. Neighborhood Cobains could now simply plug in, play, and record their sonic opera to their laptops within a few hours, give or take. Though certainly not the first of its kind, the 2i2 achieved what so many other digital audio interfaces could not: it allowed everyone to live out their rockstar fantasies, from your local goth kid to your classic rock-coded dad. It immediately supplanted similar products on the market with its balanced inputs, high headroom, and intuitive design, and it still remains a top seller and the go-to rec for beginner and intermediate musicians alike. It’s so ubiquitous now that it’s become a meme.

What is so compelling to me about the Scarlett 2i2, however, is not so much its popularity or how its technology delegated the authority of music production from center to margins per se but how this decentralization incubated the dominant sounds and attitudes of mainstream and alternative music throughout the 2010s. As the 2i2 began appearing more frequently on the desks of aspiring young musicians, it seemed to develop a timbre of its own, a particular home-baked, intimate sound that crystallized digitally into a full-fledged genre across emerging online audio distribution platforms like Bandcamp and Soundcloud.

Critics, bloggers, artists, and music fans of the 2010s quickly gave name to the Scarlett sound: bedroom pop. A questionable tag with roots in ‘90s’ cassette culture, bedroom pop, when used today, describes a kind fuzzy, lo-fi genre of music created by the extremely online, a “kind of hushed, Internet-facing electronic pop that could be kept secret from adults, rather than weaponized against them,” as Carrie Battan has it. Battan’s notion of avoidant secrecy is crucial here. Unlike American rock and roll, which got its stones rolling in greasy, gasoline-soaked garages, or emo, which flourished in the basements beneath suburban D.C. and Midwestern homes, bedroom pop finds its roots right in the room of one’s own, a domestic space often associated in aesthetics with ideas of privacy, intimacy, the quotidian, confession, rest, dreams, and I suppose now, the Internet.

However, for teenagers and young adults, who are both the primary creators and audience of bedroom pop, the space of the bedroom simultaneously imprisons and liberates. Few songs explore this conflict as effectively as the The Beach Boys’ 1963 ballad, “In My Room,” perhaps the true progenitor of the genre.

“There's a world where I can go and / Tell my secrets to,” Brian Wilson croons at the song’s beginning. His bedroom initially seems like a confidant, interactive and analeptic, but Wilson’s confession soon turns inward and gives way to worry: “Do my crying and my sighing / Laugh at yesterday?” For Wilson, who suffered from agoraphobia, the bedroom offers refuge from the challenges of the outside world but also provides him with too much guarded time to think, a dangerous thing for the sensitive person. Not to play armchair Freud, but the byproduct of this conflict between external sanctuary and internal anguish is, of course, anxiety—that suffocating terror felt after encountering oneself a little too closely. To put it simply and in a sort of millennial therapy-speak way, the titular space of “In My Room” harms by helping; the bedroom itself puts Wilson in his #feels.

It is precisely this anxiety of the nest sitting at the core of 2010s bedroom pop. Of course, I don’t mean to say that every song of the phenomenon was literally about this feeling, but the star children of the genre certainly carried with them the cozy chaos one experiences when bedroom becomes best friend. Consider the case of Orchid Tapes, without a doubt the preeminent label of this scene. In particular, recall their seminal 2014 sampler, the aptly-titled Boring Ecstasy, which features a demimonde of “artists unafraid to lean in close and expose their feelings,” as the Pitchfork review puts it. The comp brims with the fuzzy tension of a shut-in lifestyle, each song held together tenuously, always threatening to come apart under the sudden surge of mental anguish or the onset of plain old lassitude. Songs like Infinity Crush’s “Spoiled” are literally bored to death, all tape-deck drone, languidly strummed chords, and barely-there vocals that sound desperate for fresh air. “Make me bored, make me cold / Make me all alone,” “Spoiled” insists. It is the sound of emotional and physical prison.

The most recognizable artist on the comp, Alex G, has made an entire career out of this reclusive pose, but has managed to elevate it to fresh, exciting new heights that have made him a crossover star. I think it’s possible to read his 2015 album, Beach Music, as a marker for the end of the alternative bedroom pop sound you hear on Boring Ecstasy and the beginning of what I partly in jest call living room pop, a commodified rendering of the Orchid Tapes scene carefully sanitized of its anxious authenticity. Not to say that Beach Music or anything after is an example of this inferior spin-off, but it propelled Alex G into a more mainstream audience that gradually adopted his style. It reached number 9 on Billboard’s Heatseekers chart, and it also landed him writing credits on Frank Ocean’s insanely popular 2016 masterpiece, Blond.

DIY had officially reached the masses. From there, more and more Alex G and Frank doppelgängers began appearing across all avenues of mainstream culture, and bedroom pop became the pop. Artists like Clairo and Boy Pablo racked up millions and millions of views on YouTube with their lo-fi ditties about Cheetos and texting, while old heads like Mitski and TV Girl, both longtime orbiters of the Orchid Tapes world, soared into the mainstream and mainstream-adjacent spotlights. Bedroom pop reached its normie apex in 2019, however, with the advent of Billie Eilish, whose initial marketing hook—that her songs were recorded in a makeshift bedroom studio—helped launch her to megastardom. By 2020, the handmade aesthetics of bedroom pop had spread to nearly every corner of mass culture, from fashion to filmmaking. It was no longer a scene.

Today, at age 30, I consider the genre mostly washed with a few exceptions, its mainstream reproduction utterly boring and the alternative original lacking in vitality. I just don’t really keep up with it anymore—you feel me?

That said, I’ve always been a sucker for bedroom pop album covers (all those grainy polaroids and cozy suburban scenes), so when I saw the artwork for Hourglass by idialedyournumber posted on the IG story of an old favorite DJ of mine, Ryan Hemsworth, I decided to pop it on—and wow, was I impressed.

Hailing from Halifax, Nova Scotia (like Hemsworth himself), idialedyournumber is the solo project of teenager Jessie Everill, and it’s probably the first exciting DIY act I’ve heard since the days of Orchid Tapes. Everill belongs to the burgeoning “pier emo” scene in Nova Scotia, a collective of young artists defamiliarizing conventional bedroom pop and Midwest emo with stylings pulled from a diverse range of genres, from skramz and noise to hyperpop and chiptune to folk and jam music. Hourglass is genuinely exceptional, though, in its syncretism, succeeding where so many other records of its terminally online ilk fall short. For example, consider album opener, “Bunny Goes 2 Business School.” It’s anchored by a simple downcast emo riff you’d hear on any old Broken World release, but Everill douses it in 8-bit distortion and reinforces its clipped-out texture with a looped industrial beat that chugs forward in a dizzying, metallic spiral. The result is something like Jane Remover meets NIN meets iwrotehaikusaboutcannibalisminyouryearbook.

Also noteworthy is “The Home We Built is Gone,” a post-genre gem that layers compressed blasts of screamo vocals across an inventive foundation comprising fuzzy toy synths and a crunchy acoustic guitar loop nearly identical to the main riff in, surprisingly, Vampire Weekend’s “Harmony Hall.” By the song’s climax, Everill’s screaming relaxes into a rappy speak-sing, punctuating the whole thing with a faint stamp of pop punk that just sticks with you. Throughout its two-and-a-half-minute duration, you can hear the contours and stylings of skramz, indie pop, folk, synth pop, and emo collide against each other and, at times, merge seamlessly into something genuinely distinctive. It is really one of the coolest songs I’ve heard in a while. “Grandfather” is another kaleidoscopic barrage, a one-minute sizzler of feedback drone, overdriven shrieks, and—once again—sugary indie pop synths that feel perfectly out of place. “Hourglass” hinges solely on a voicemail/voiceover setup; it’s a gamble but it works.

When Everill ditches the aggro genre-smashing for more traditional sounds, she makes top-notch bedroom pop that would fit nicely on a classic tape like Boring Ecstasy. “Goodnight, Etc.” is a warbling relationship ballad set over a bittersweet Gameboy beat. Its melody ebbs and flows with a clear-headed elegance that sort of reminds me of a Nintendo’d take on Bic Runga’s underrated 1997 contribution to the American Pie soundtrack. “Interlude (I Grow Awake)” is exactly what its title suggests, an interlude, but is similarly well-crafted. “Susie” is a restrained, straightforward bedroom pop jammer a la Soccer Mommy that proves Everill is capable of wearing well yet another sonic mask. The final track, “I Am No Longer In Control of My Body,” is a nice send-off, a gentle noodly slowburn left out too long in the sun.

Above idialedyournumber’s stylistic remixing, however, lies a genuine understanding of what makes bedroom pop, and also emo, appealing to its fans; it makes bearable that fuzzy anxiety of the nest we all endure at some point during young adulthood. Hourglass reminds me very much of the essential records from both genres, stuff like Teen Suicide’s I Will Be My Own Hell Because There Is A Devil Inside My Body and Merchant Ships’ For Cameron. To be sure, Hourglass is indeed a young album created by a young artist, and as such, it may sound juvenile to some listeners, particularly those reading here. To each there own, sure, but I’d also urge skeptics of idialedyournumber, and thus naysayers of bedroom pop and emo at large, to suspend their more dusty impulses and recall their own memories of their experiences with the fury of youth. Hourglass is one of those rare records that reminds me exactly why I trudged my ass to Guitar Center in 2013 to empty my savings on a Scarlett 2i2.

Buy a digital copy of Hourglass here. Also, check out idialedyournumber’s label, Warm Walk Records, here.